Scientists say they have recovered the oldest known Homo sapiens DNA from human remains found in Europe, and the information is helping to reveal our species’ shared history with Neanderthals.

The ancient genomes sequenced from 13 bone fragments unearthed in a cave beneath a medieval castle in Ranis, Germany, belonged to six individuals, including a mother, daughter and distant cousins who lived in the region around 45,000 years ago, according to the study that published Thursday in the journal Nature.

The genomes carried evidence of Neanderthal ancestry. Researchers determined that the ancestors of those early humans who lived in Ranis and the surrounding area likely encountered and made babies with Neanderthals about 80 generations earlier, or 1,500 years earlier, although that interaction did not necessarily happen in the same place.

Scientists have known since the first Neanderthal genome was sequenced in 2010 that early humans interbred with Neanderthals, a bombshell revelation that bequeathed a genetic legacy still traceable in humans today.

However, exactly when, how often and where this critical and mysterious juncture in human history took place has been hard to pin down. Scientists have believed interspecies relations would have occurred somewhere in the Middle East as a wave of Homo sapiens left Africa and bumped into Neanderthals, who had lived across Eurasia for 250,000 years.

A broader study on Neanderthal ancestry, published Thursday in the journal Science, that analyzed information from the genomes of 59 ancient humans and those of 275 living humans corroborated the more precise timeline, finding that the majority of Neanderthal ancestry in modern humans can be attributed to a “single, shared extended period of gene flow.”

“We were far more similar than we were different,” Priya Moorjani, a senior author of the Science study and an assistant professor in the department of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley, said at a news briefing.

“The differences that we imagined between these groups to be very big, actually, were very small, genetically speaking. They seem to have mixed with each other for a long period of time and were living side by side for a long period of time.”

The research pinpointed a pivotal period that began about 50,500 years ago and ended around 43,500 years ago — not long before the now extinct Neanderthals began to disappear from the archaeological record. Over this 7,000-year time frame, early humans encountered Neanderthals, had sex and gave birth to children on a fairly regular basis. The height of the activity was 47,000 years ago, the study suggested.

The research also showed how certain genetic variants inherited from our Neanderthal ancestors, which make up between 1% and 3% of our genomes today, varied over time. Some, such as those related to the immune system, were beneficial to humans as they lived through the last ice age, when temperatures were much cooler, and they continue to confer benefits today.

The two studies lend “substantial confidence” to the timing of when humans and Neanderthals exchanged genes, something geneticists describe as introgression, said evolutionary geneticist Tony Capra, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics in the Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute at the University of California, San Francisco.

“Genetic data from this crucial period in our evolution are very rare,” said Capra, who wasn’t involved in the research, via email. “These studies underscore how having even a few ancient genomes provides powerful perspective that enabled the authors to refine our understanding of human migration and Neanderthal introgression.”

The scientists working on the two research projects decided to publish their work at the same time when they realized they had separately reached a similar conclusion.

How Neanderthal ancestry has shaped human genes

The research in Science found that genetic variants inherited from our Neanderthal ancestors are unevenly distributed across the human genome.

Some regions, which the scientists call “archaic deserts,” are devoid of Neanderthal genes. These deserts likely developed quickly after the two groups interbred, within 100 generations, perhaps because they resulted in birth defects or diseases that would have affected the survival chances of the offspring.

“It suggests that hybrid individuals who had Neanderthal DNA in these regions were substantially less fit, likely to due to severe disease, lethality, or infertility,” Capra said via email.

In particular, the X chromosome was a desert. Capra said the effects of Neanderthal variants that cause disease could be greater on the X chromosome, perhaps because it is present in two copies in females, but only present in one copy in males.

“The X chromosome also has many genes that are linked to male fertility when modified, so it has been proposed that some of this effect could have come from introgression leading to male hybrid sterility,” he said.

The Neanderthal gene variants detected most frequently in ancient and modern Homo sapiens genomes are related to traits and functions that included immune function, skin pigmentation and metabolism, with some increasing in frequency over time.

“Neanderthals were living outside Africa in harsh, ice age climates and were adapted to the climate and to the pathogens in these environments. When modern humans left Africa and interbred with Neanderthals, some individuals inherited Neanderthal genes that presumably allowed them to adapt and thrive better in the environment,” said Leonardo Iasi, co-lead author of the Science paper and a doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

The individuals living at Ranis had 2.9% Neanderthal ancestry, not dissimilar to most people today, the Nature study found.

The new timeline allows scientists to understand better when humans left Africa and migrated around the world. It suggested that the main wave of migration out of Africa was essentially done by 43,500 years ago because most humans outside Africa today have Neanderthal ancestry originating from this period, the Science study suggested.

However, there is still much scientists don’t know. It’s not clear why people in East Asia today have more Neanderthal ancestry than Europeans, or why Neanderthal genomes from this period show little evidence of Homo sapiens DNA.

While the genomes sequenced from the Ranis individuals are the oldest Homo sapiens ones, scientists have previously recovered and analyzed DNA from Neanderthal remains that date back 400,000 years.

Lost branch of the human family tree

The individuals who called the cave in Ranis home were among the first Homo sapiens to live in Europe.

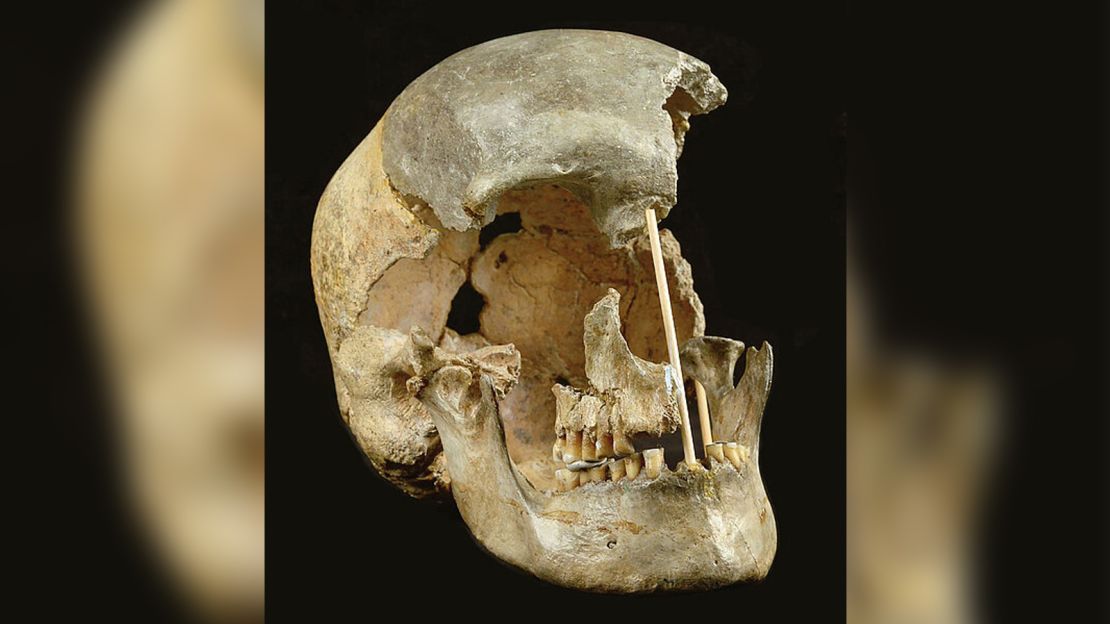

These early Europeans numbered a few hundred and included a woman who lived 230 kilometers (143 miles) away in Zlatý kůň in the Czech Republic. DNA from her skull was sequenced in a previous study, and researchers involved in the Nature study were able to connect her to the Ranis individuals.

These individuals had dark skin, dark hair and brown eyes, according to the study, perhaps reflecting their relatively recent arrival from Africa. Scientists are continuing to study remains from the site to piece together their diet and how they lived.

The family group was part of a pioneer population that eventually died out, leaving no trace of ancestry in people alive today. Other lineages of ancient humans also went extinct around 40,000 years ago and disappeared just like the Neanderthals ultimately did, said Johannes Krause, director at the department of archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. These extinctions may suggest that Homo sapiens did not play a role in the demise of Homo neanderthalensis.

“It’s kind of interesting to see that human story is not always a story of success,” said Krause, a senior author of the Nature study.

By Katie Hunt, CNN