A small silver amulet discovered by archaeologists in Germany could transform our understanding of how Christianity spread under the Roman Empire, experts have said.

The tiny artefact, which measures about 1.4 inches (3.6 centimeters) long, was unearthed in a 3rd-century Roman grave just outside Frankfurt back in 2018.

Archaeologists discovered it on the skeleton of a man buried in a cemetery in the Roman city of Nida, one of the largest and most important sites in the central German state of Hesse. However, it has taken until now for researchers to be able to examine a thin silver foil that was found inside it.

Alongside other artefacts in the grave, such as an incense burner and a jug made of clay, the amulet was found under the skeleton’s chin. Also known as a phylactery, it was probably worn on a ribbon around the man’s neck to provide spiritual protection.

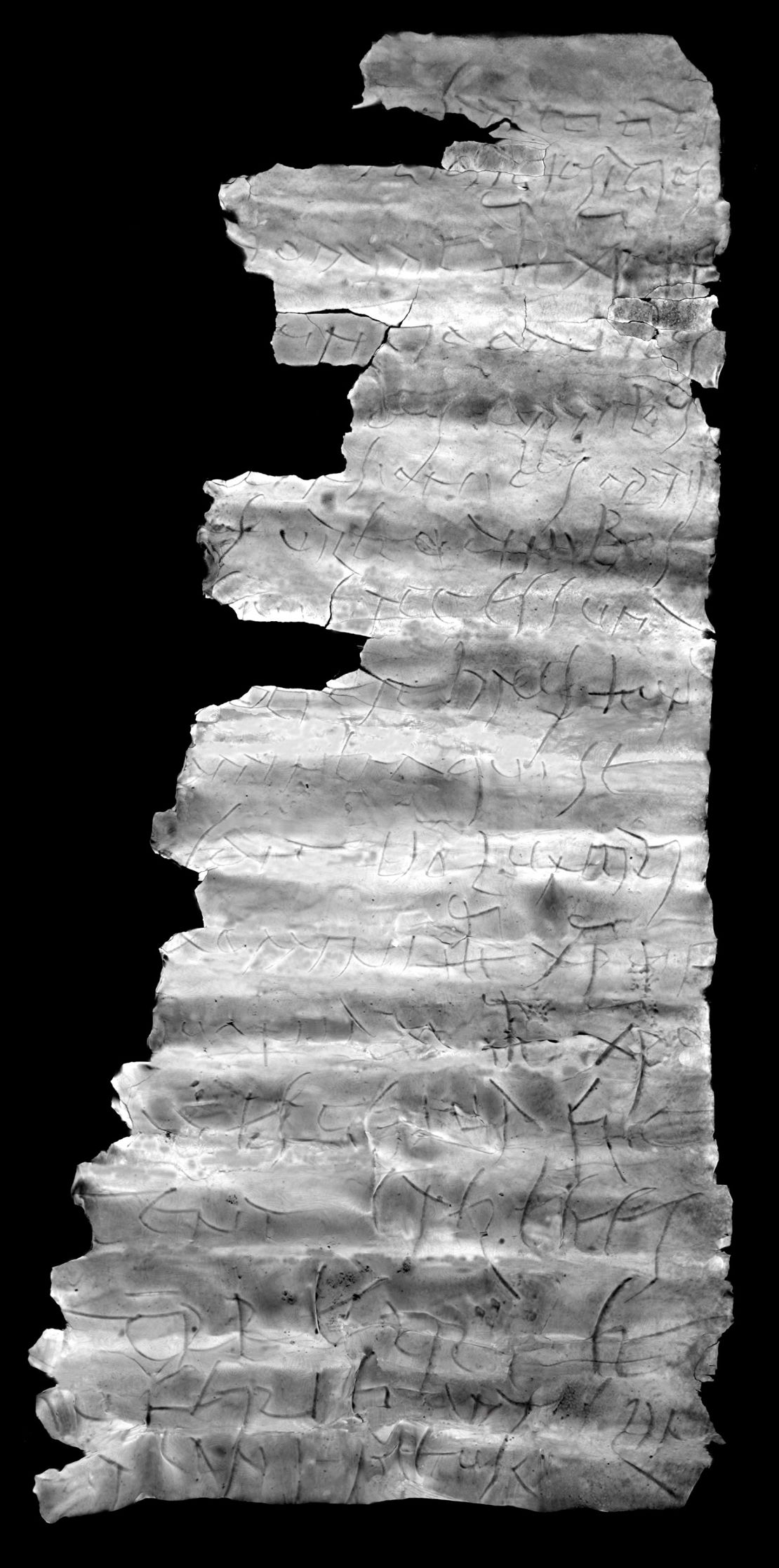

The “hair-thin” foil inside the amulet was so brittle that it would have simply disintegrated if researchers had tried to unfurl it. However, microscopic examinations and X-rays carried out back in 2019 showed that there were words engraved on it.

It took a further five years before the team at the Archaeological Museum Frankfurt figured out a way to decipher what they said.

Alongside other artefacts in the grave, such as an incense burner and a jug made of clay, the amulet was found under the skeleton’s chin. Also known as a phylactery, it was probably worn on a ribbon around the man’s neck to provide spiritual protection.

The “hair-thin” foil inside the amulet was so brittle that it would have simply disintegrated if researchers had tried to unfurl it. However, microscopic examinations and X-rays carried out back in 2019 showed that there were words engraved on it.

It took a further five years before the team at the Archaeological Museum Frankfurt figured out a way to decipher what they said.

The breakthrough came in May of this year, when researchers at the Leibniz Center for Archaeology in Mainz (LEIZA) used CT scanners to analyze the foil.

Ivan Calandra, head of the imaging laboratory at LEIZA, explained the process in a press statement.

“The challenge in the analysis was that the silver sheet was rolled, but after around 1,800 years it was of course also creased and pressed. Using CT, we were able to scan it at a very high resolution and create a 3D model.”

It was only through this process of digitally unrolling the sheet that the entire text became visible and could then be deciphered. What the researchers discovered astounded them.

Earliest evidence of Christianity

There on the foil were 18 lines of Latin text that repeatedly referenced Jesus, as well as St. Titus, a disciple and confidant of St. Paul the Apostle.

As the grave in which the amulet was found dates back to somewhere between 230 and 270 AD, the amulet has emerged as the earliest evidence of Christianity in Europe north of the Alps. All previous discoveries are from at least 50 years after this, according to the statement.

At the time of the burial, Christianity was becoming an increasingly popular sect but identifying as a Christian was still risky. Clearly the buried man, who is thought to have been aged 35 to 45, felt his faith so strongly that he took it to the grave with him.

Markus Scholz, an archaeologist and expert in Latin inscriptions and professor at Frankfurt’s Goethe University, painstakingly deciphered the text of the “Frankfurt Silver Inscription,” as it is known.

Describing the complicated process in the statement, he said: “Sometimes it took me weeks, even months, to come up with the next idea. I called in experts from the history of theology, among others, and bit by bit we worked together to approach the text and finally decipher it.”

The fact that the writing was entirely in Latin was very unexpected, he said.

“This is unusual for this period. Normally, such inscriptions on amulets were written in Greek or Hebrew.”

When translated into English, the text reads:

“(In the name?) of St Titus.

Holy, holy, holy!

In the name of Jesus Christ, Son of God!

The Lord of the World

Resists (to the best of his ability?)

All attacks(?)/setbacks(?).

The God(?) grants the well-being

Entry.

This means of salvation(?) protects

The human being who

Surrenders to the will

Of the Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God,

Since before Jesus Christ

All knees bow to Jesus Christ: the heavenly

The earthly and

The subterranean and every tongue

Confess (to Jesus Christ).”

There is no reference in the text to any other faith besides Christianity, which would also have been unusual at this time.

According to the Frankfurt archaeology museum, reliable evidence of Christian life in the northern Alpine regions of the Roman Empire only goes as far back as the 4th century AD.

‘Fantastic find’ made possible by modern technology

Wolfram Kinzig, a church historian and professor from the University of Bonn, helped Scholz to decipher the inscription.

The “silver inscription is one of the oldest pieces of evidence we have for the spread of the New Testament in Roman Germania, because it quotes Philippians 2:10–11 in Latin translation,” Kinzig explained in an interview published on the University of Bonn’s website.

“It’s a striking example of how Biblical quotations were used in magic designed to protect the dead,” said Kinzig.

Peter Heather, a professor of medieval history at King’s College London with a specialist interest in the evolution of Christianity, described the discovery as a “fantastic find.”

Heather, who wasn’t involved in the research, told CNN: “The capacity to be able to decipher the writing on that rolled-up piece of silver is extraordinary. This is something that’s only possible now with modern technology. If they’d found it 100 years ago they wouldn’t have known what it was. Silver amulets are probably going to contain some kind of magical scroll but you don’t know what – it could be any religion.”

He added: “You’ve got evidence of Christian communities in more central parts of the empire but not in a frontier town like that in Roman Germany so that is very unusual, well it’s unique. You’re pushing the history of Christianity in that region back.”

By Lianne Kolirin, CNN