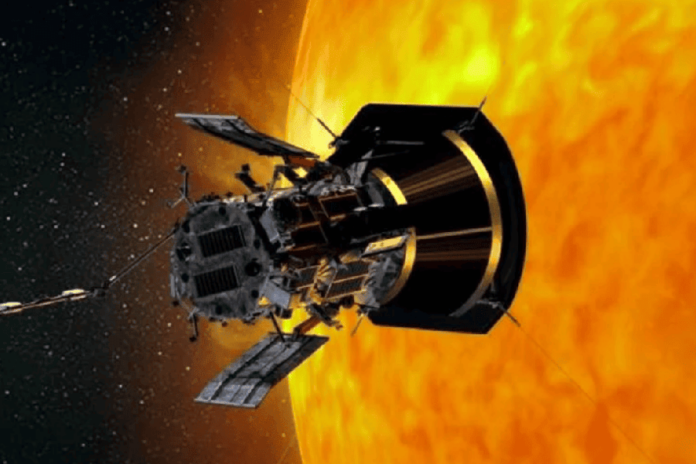

The Parker Solar Probe was set to zoom by the sun on Tuesday during a record-breaking flyby, coming within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) of the solar surface during humanity’s closest approach to a star.

The uncrewed spacecraft was expected to fly at 430,000 miles per hour (692,000 kilometers per hour), which is fast enough to reach Tokyo from Washington, DC, in under a minute, according to NASA. The speedy flyby would make the probe the fastest human-made object in history, the agency shared December 16 during a NASA Science Live presentation on YouTube.

The mission has been building up to this historic milestone since it launched on August 12, 2018 — an event attended by the probe’s namesake, Dr. Eugene Parker, an astrophysicist who pioneered the solar research field of heliophysics.

Scott Olson/Getty Images

Parker was the first living person to have a spacecraft named after him. The astrophysicist, whose research revolutionized humanity’s understanding of the sun and interplanetary space, died at age 94 in March 2022. But he was still able to witness how the spacecraft could help solve mysteries about the sun more than 65 years after the mission was originally envisioned.

The probe became the first spacecraft to “touch the sun” by successfully flying through the sun’s corona, or upper atmosphere, to sample particles and our star’s magnetic fields in December 2021.

Over the last six years of the spacecraft’s seven-year mission, the Parker Solar Probe has collected data to enlighten scientists about some of the sun’s greatest mysteries.

Heliophysicists have long wondered how the solar wind, a constant stream of particles released by the sun, is generated as well as why the sun’s corona is so much hotter than its surface.

Scientists also want to understand how coronal mass ejections, or large clouds of ionized gas called plasma and magnetic fields that erupt from the sun’s outer atmosphere, are structured.

When these ejections are aimed at Earth, they can cause geomagnetic storms, or major disturbances of the planet’s magnetic field, that can affect satellites as well as power and communication infrastructure on Earth.

Now, the time has come for Parker’s closest and final flybys, which could complete the answers to these enduring questions and uncover new mysteries by exploring uncharted solar territory.

“Parker Solar Probe is changing the field of heliophysics,” said Helene Winters, Parker Solar Probe’s project manager from Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, in a statement. “After years of braving the heat and dust of the inner solar system, taking blasts of solar energy and radiation that no spacecraft has ever seen, Parker Solar Probe continues to thrive.”

A blisteringly close flyby of a fiery star

Parker’s flyby at around 6:53 a.m. ET on Christmas Eve was planned as the first of the spacecraft’s final three closest approaches, with the other two expected to occur on March 22 and June 19.

The spacecraft was expected to get so close to our star that if the distance between Earth and the sun were the length of an American football field, the spacecraft would be about 4 yards from the end zone, according to NASA.

At this proximity, the probe would be able to fly through plumes of plasma as well as within a solar eruption if one releases from the sun.

The spacecraft was built to withstand the extremes of the sun and has flown through coronal mass ejections in the past with no impact to the vehicle, said Parker Solar Probe project scientist Nour Rawafi.

The spacecraft is equipped with a carbon foam shield that is 4.5 inches (11.4 centimeters) thick and 8 feet (2.4 meters) wide. On Earth before launch, the shield was tested and able to withstand temperatures near 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (nearly 1,400 degrees Celsius). On Christmas Eve, the shield could face temperatures up to 1,800 F (980 degrees C).

Meanwhile, the spacecraft’s interior will be at a comfortable room temperature so the electronics systems and science instruments can operate as expected. A unique cooling system designed by the Applied Physics Laboratory pumps water through the craft’s solar arrays to keep them at a steady temperature of 320 F (160 C), even during close approaches to the sun.

The spacecraft was set to conduct its flyby autonomously because mission control is out of contact with the probe due to its proximity to the sun.

After the closest approach, around midnight between Thursday and Friday, Parker will send a signal called a beacon tone back to mission control to confirm the success of the flyby, Rawafi said.

The beacon tone is a limited piece of data that relays the overall state of the spacecraft, he said.

The immense set of data and images gathered during the flyby won’t become available to mission control until Parker has moved away from the sun in its orbit, which will occur about three weeks later in mid-January, Rawafi said.

Perfect timing to see an active sun

Just over a year after the Parker Solar Probe first launched, the sun entered a new solar cycle. Now, as Parker makes its closest approach, the sun is experiencing solar maximum, meaning that the mission has had a chance to witness most of a solar cycle and the transitions between its highs and lows, said Dr. C. Alex Young, associate director for science in the Heliophysics Science Division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Scientists from NASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the international Solar Cycle Prediction Panel announced in October that the sun has reached solar maximum, or the peak of activity within its 11-year cycle.

At the peak of the solar cycle, the sun’s magnetic poles flip, causing the sun to transition from calm to active. Experts track increasing solar activity by counting how many sunspots appear on the sun’s surface. And the sun is expected to remain active for the next year or so.

The sun’s increasing activity became obvious this year during two major displays of auroras on Earth in May and October, when coronal mass ejections released by the sun were directed at our planet. The solar storms are also responsible for generating auroras that dance around Earth’s poles, known as the northern lights, or aurora borealis, and southern lights, or aurora australis. When the energized particles from coronal mass ejections reach Earth’s magnetic field, they interact with gases in the atmosphere to create different colored light in the sky.

“Both of those storms caused auroras to be visible down to the very bottom of the United States,” Young said. “But the May storm was an especially strong storm. In fact, we think it could be a 100- to possibly 500-year event, and that caused auroras very close to the equator, which is extremely unheard of. It was a worldwide event that millions and, hopefully billions, of people, were able to see, and it may not happen again.”

The data gathered by Parker Solar Probe could enable scientists to better understand solar storms and even how to predict them, Young said.

“The sun is the only star that we can see in detail, but we can actually go to and measure it directly,” Young said. “It’s a laboratory in our solar system that allows us to learn about all the other stars in the universe and how all those stars interact with the billions and billions of other planets that may or may not be like our own planets in our solar system.”

The Parker Solar Probe will continue orbiting closely to the sun over the next six months. NASA/Johns Hopkins APL

With that in mind, Rawafi said he hopes that the sun puts on a spectacular show during the probe’s close approaches, enabling scientists to gain insights into the sun’s activity.

“Sun, please do your best,” Rawafi said. “Give us the strongest event you can do, and the Parker Solar Probe can deal with it.”

By Ashley Strickland, CNN