Two weeks after the election, a gathering in Gettysburg commemorated Lincoln’s address, 272 words that have come to epitomize what it means to be presidential.

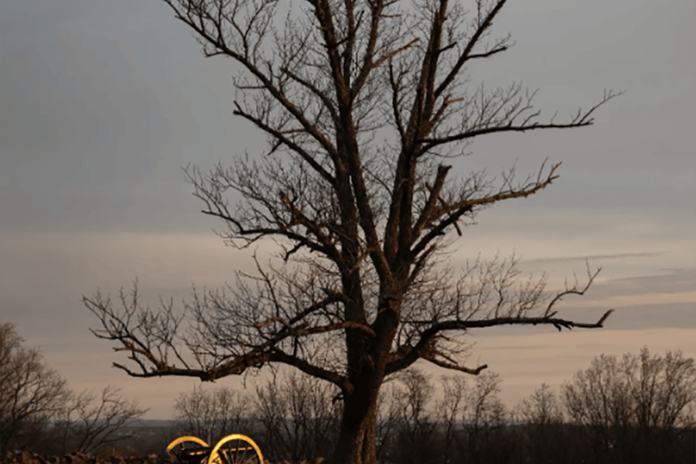

The bugler’s call to assemble had sounded, wreaths had been laid, a choral society had sung and dignitaries had spoken, all on a blood-consecrated hill in the Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg. All to commemorate the 161st anniversary of the speech that came to epitomize what it meant to be presidential.

On Nov. 19, 1863, on this very hill, President Abraham Lincoln unfolded his six-foot-four frame to stand and dedicate a national soldiers’ cemetery made necessary by the horrific Battle of Gettysburg just four months earlier. His 272 words became a civic prayer of unity and purpose for a nation riven by civil war: the Gettysburg Address.

Now, exactly two weeks after a contentious presidential election that seemed only to widen the American divide, it was the daunting honor of a Lincoln scholar named Harold Holzer to channel the 16th president and recite his immortal words. He, too, is bearded, but he grew up in the borough of Queens, not the woods of Kentucky, and he stands five-foot-nine, maybe.

Mr. Holzer knew the address almost as well as he knew the Shema, the Jewish prayer. Even so, he had fretted in the days leading up to this moment. “I don’t have the voice for it,” he had said.

The timing of the ceremony, so soon after the election of a once and future president, left Mr. Holzer mourning how starkly the understanding of “presidential” had changed between then and now. Between a man known as “Honest Abe” and a man with 34 felony convictions; between one who summoned “the better angels of our nature” and one who referred to his opponent as “retarded” and undocumented immigrants as “poisoning the blood of our country.”

“Heartbreaking,” Mr. Holzer said.

On that distant day, mild like this one, Lincoln and other dignitaries had assembled on a creaking wooden platform at the edge of the town cemetery. Reflections of the three July days of bloodshed, culminating in more than 50,000 casualties, were all around — the bullet-pocked buildings, the cannon-scarred fields, the shell-fragment souvenirs sold along the roadside. The transformed town had been left to contend with thousands of dead and dying soldiers.

The invitation Lincoln received to deliver “a few appropriate remarks” had been an afterthought. A prominent orator, Edward Everett, had already been chosen to deliver the keynote address, and when it came time, the man gave it his all: nearly two hours of classical allusion, detailed description and sentiment.

Then the president, aged by war and the loss of a dear son, ridiculed by some as coarse and apelike, rose. In a clear but reedy voice he began — “Four score and seven years ago” — and finished in about two minutes. He sat down, convinced that his brief words had not found purchase.

Now, a couple of hundred yards from where Lincoln had stood, Mr. Holzer sat among other V.I.P.s on a bunting-adorned rostrum that faced several hundred guests in foldout chairs as white as the tombstones in the distance. Most were in casual clothes; a few wore Civil War-era attire; at least one wore a MAGA hat.

Mr. Holzer wore a tweed jacket, gray pants and, beneath those pants, long johns. Having attended many of these annual commemorations, organized by the Lincoln Fellowship of Pennsylvania, he knew the bite of the November winds that blow across the somber grounds.

He had served many roles over his 75 years: newspaper reporter, press officer for Gov. Mario M. Cuomo of New York, museum executive and, currently, director of the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College in Manhattan. He had written and edited more than 50 books, nearly all centering on Lincoln and his era, and — come to think of it, he was no longer that nervous.

But before Mr. Holzer could approach the lectern, an annual ceremony within this annual ceremony had to take place. Sixteen people from eight countries — Bhutan, Britain, the Dominican Republic, Ghana, Guatemala, India, Mexico and South Africa — stood as one.

By Dan Barry from Gettysburg, Pa.

Photographs by Todd Heisler