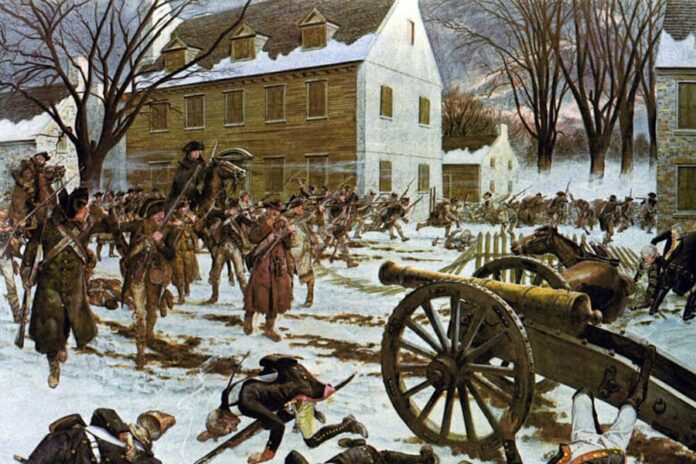

It is a story so well known it has become a meme. “Americans: Willing to cross a frozen river to kill you in your sleep on Christmas.” George Washington’s Continental Army, having suffered a series of major setbacks in the fighting around New York City in the summer and fall of 1776, launched a surprising counterattack on Dec. 26, 1776. Crossing the icy Delaware River on Christmas night, Washington’s army surprised and captured almost 1,000 brutal Hessian mercenaries, drunk from Christmas celebrations. These troops were fighting on the British side, sent to America by their greedy monarchs. The victory over these drunken mercenaries raised the morale of the Continental Army, convincing many of the patriots to stay on and reenlist for an additional six weeks. As a result, future battles hinged on the success of Trenton, making this a turning point in the war. In this telling, a free army of American citizen-soldiers triumphed over the hireling corruption of European despotism. Ergo, a sort of American Christmas miracle.

The trouble is, many elements of this familiar story aren’t quite right. They rely on an overly simplistic understanding of the Revolutionary War. The story above is part of America’s heritage, but not quite part of American history. In the Christmas season, it can be easy to reach for the comforting. Stories that go beyond fact into myth can tell us important truths about who we are, but they can also distract us and lead to false or hazy understandings of military history and military affairs. This Christmas, let’s cut through a bit of myth in order to gain a better understanding of the reality of America’s founding. By trying to move past the heritage to the history, we can find out more about our enemies and ourselves. Only by giving the Hessians their due can we appreciate the true nature of Washington’s wisdom.

Who Were the Hessians?

Carefully understanding our enemies is an important first step. Who were the Hessians? George Washington’s German opponents have long been obscure, but the research of scholars like Friederike Baer and Daniel Krebs is making them tangible.

Of the many myths regarding the Revolutionary War, none seem as widespread as the idea that the “Hessians” were “mercenaries.” First off, they weren’t all Hessian. Although most came from the mid-sized state of Hessen-Kassel, there were also troops from the principalities of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, Hessen-Hanau, Ansbach-Bayreuth, Waldeck, and Anhalt-Zerbst. And if you look at the larger global war, of which the revolution was a part, troops from the state of Hanover (Braunschweig-Lüneburg) also fought for the British in such far-flung locales as Gibraltar and India. So, while over 60 percent of the “Hessians” came from Hessen, the other 40 percent hailed from all over the western and central Holy Roman Empire — roughly where Germany is today.

Also, these troops, Hessians and others, weren’t quite mercenaries. This is a tough one to swallow, and this misconception is even included in the Declaration of Independence. Don’t believe me? Imagine you are a soldier in the 1980s U.S. Army, serving in West Germany during the Cold War. You are stationed there because of longstanding agreements and alliances. The United States and the West German government have a financial understanding that helps provide for your stationing there. Are you a mercenary?

The situation was very similar for the German-speaking soldiers who fought in the American War of Independence, They had a longstanding relationship with Great Britain, stretching back decades. As a result of the Hanoverian succession in 1714 (the British royal family was drawn from Hanover), their leaders had marriage ties with Great Britain. Horace Walpole, a British politician from the 1730s, referred to the Hessians as the Triarii of Great Britain: its reliable last line of defense. These soldiers did not personally or corporately take on contracts from the British; they were members of their state militaries. Their governments were paid a subsidy by the British in order to fight in their wars.

Many of them, like some of the American troops they fought against, volunteered for economic reasons. Others, like some of the British troops they fought alongside and some of the Americans across the battlefield, were conscripted soldiers. For this reason, the modern German term for these troops is Subsidientruppen, or subsidy troops. Thus, it might be better to speak of the German-speaking subsidy troops, as opposed to calling them Hessians or mercenaries.

The mercenary relationship, if one existed at all, was between the British and the rulers of these states. As a result, you often hear that these troops were sold to fight in North America because their princes were greedy and wanted to build palaces and pay for their illegitimate children. This, too, ignores the realities behind these policies. The princes of the western Holy Roman Empire lived in an incredibly dangerous world during the 18th century. Their territories were small, rural principalities, trapped between the military giants of France, Austria, and Prussia. As a result, from the 1670s on, 100 years before the American Revolution, these princes used subsidy contracts to build themselves larger armies. This preserved their independence. These subsidy contracts were a standard feature of European politics, diplomacy, and conflict resolution. They allowed the princes to better protect their small domains. None of the princes who formed subsidy contracts with Britain during the American War of Independence were doing something radically new or greedy. Instead, the money from subsidy contracts was often poured back into the army, in order to create a larger military to protect these small nations from the French.

Some rulers even used the subsidy funds to promote their economy. The Hessian (Hessen-Kassel) Landgraf Friedrich II actually used the funds from the contract, in part, to promote economic development and the textile industry in his territories. Now, not all of these princes were the same. Some of them had illegitimate children. Some had opulent palaces. But portraying them as sex-crazed misers limits our understanding of the economic and security necessities that actually underpinned their subsidy policies. For over a hundred years, from the 1670s to the French Revolution, these policies maintained the survival and independence of these states.

If these troops weren’t all Hessians or mercenaries, were they particularly prone to brutality or drink? English officers in the Seven Years’ War noted that their troops were reprimanded for plundering more than Hessian forces were. During the War of Independence, the Hessians once again behaved better than their British counterparts. Although there was a surge of fear about Hessian brutality early in the war, after the first few years of the fighting, American civilians believed that the subsidy troops treated them better than British soldiers did. The American soldier and future vice president Aaron Burr wrote of Hessian atrocities: “Various have been the reports concerning the barbarities committed by the Hessians, most of them [are] incredible and false.” Hessian troops committed crimes in America, there is no doubt. What is clear is that these crimes were not excessive for an 18th-century conflict.

And what about the state of Hessian soldiers, supposedly drunk from Christmas celebrations when Washington arrived? John Greenwood, a 16-year-old soldier in a Massachusetts regiment, recalled, “I am certain not a drop of liquor was drunk the whole night … and I am willing to go on oath that I did not see a solitary drunken soldier belonging to the enemy.” As Greenwood’s regiment assaulted the Hessians at close range and he guarded Hessian prisoners of war after the battle, he was in a good position to speak with authority. The myth of the Hessians stemmed from stereotypical American attitudes in the 1770s, which saw German Christmas celebrations as a bit over the top. One American officer wrote: “They make a great deal of Christmas in Germany, and no doubt the Hessians will drink a great deal of beer and have a dance to-night.” Only, as Greenwood attests, they did not.

Christmas: A Battle and a Compromise

Regardless of the state of the Hessian garrison, Washington’s plan was bold. Employing cutting-edge European tactical arts, he devised an attack where multiple independent columns would converge on Trenton, bringing around 6,000 men to attack the Hessian force of roughly 1,500. In the event, due to the weather and novelty of this type of operation, only around 2,400 Americans arrived. They began their attack, aided in the knowledge that the wet weather would hamper Hessian defensive fire. Both Hessian and American combatants reported trouble with their firearms as a result of weather.

Indeed, the fighting at Trenton was heavy. Despite American claims that they suffered no killed in action at Trenton, multiple Hessian officers reported seeing American dead on the ground after the battle. Were they mistaken, or were they lying to protect their reputation? Were the low American casualty figures part of an information operation to boost morale? It is difficult to say with certainty.

In their narratives of the battle, Hessian officers criticized American tactics, particularly their tendency to fire too early. Hessian officer Andreas Wiederholdt recalled:

“he had seen about 60 men of the rebels coming over to him, out of the wood about 200 paces away on the road to John’s Ferry, and they had three times fired on his picket. At first, he had not fired in return, because he thought them too far off, as they fired for the third time he ordered his picket likewise to fire on the enemy.”

In other portions of their accounts, Hessian officers reported executing complex maneuvers such as deploying skirmishers as a screen to keep the Americans at a distance, in order to give their men time to escape. This tactical complexity didn’t work: the skirmishers were driven in due to malfunctioning muskets. Even almost 250 years later, the frustration of Hessian officers comes through in these documents. For all their professional excellence, they couldn’t tactically fight their way out of a bad operational situation. They surrendered in mass.

The American army was justly pleased with the results of Washington’s counter-offensive. They had restored the army’s pride. This is sometimes used as shorthand for the story of American soldiers patriotically reenlisting after the battle. In this telling, victory on the battlefield motivated soldiers to stay. This is partially true. Washington and his subordinate commanders were desperately negotiating with their men to stay on and fight. But they still had a lot of convincing to do, even after the victory at Trenton.

Washington, having provided a tangible example of success, also had to meet the material needs of his soldiers. He raised the morale of his troops with patriotic exhortations, but he also promised them a significant reenlistment bonus. Washington was relatively upbeat about this in his report to Congress, stating that he had “engaged a number of the Eastern troops [New Englanders] to stay six weeks beyond their term of Inlistment, upon giving a bounty of ten dollars. This I know is a most extravagant price.” He was more direct in a letter to John Hancock on Wednesday, January 1:

“After much persuasion and the exertions of their Officers, half or a greater proportion of those from the Eastward, have consented to stay Six Weeks, on a bounty of Ten Dollars. I feel the inconvenience of this advance, and I know the consequences which will result from it; But what could be done? Pennsylvania had allowed the same to her Militia, The Troops felt their importance, and would have their price. Indeed as their aid is so essential and not to be dispensed with, it is to be wondered, they had not estimated it at a higher rate.”

Here, Washington fell back not on the patriotic feelings of the citizen-soldier, but on the promise to provide for material needs. This type of negotiated authority was common in most European militaries. Washington agreed to meet the material needs of his men and earned their loyalty as a result. Facing the prospect of a decline of enlistments, he did not assert that material needs were a discipline problem.

Conclusion

Like many comforting Christmas stories, the battle of Trenton has been wrapped in layers of myth. What lessons does the real battle of Trenton offer military practitioners in the 21st century? Lazy or essentialist thinking about “who we are” or who the enemy is rarely leads to accurate results. Instead, America’s enemies frequently make choices and policy decisions that make sense when they are understood in context. Far from being brutal drunken mercenaries, the Hessian soldiers George Washington faced down in December 1776 were professional soldiers with history and values of their own. Washington’s bold and innovative operational planning put them into a difficult situation, where despite their tactical acumen, they were captured. Washington appears in this story as a leader with the vision and operational brilliance to give his men an inspiring victory, but also the flexibility to negotiate and meet their material needs. All in all, it was a Christmas that America would never forget.

By Alexander Burns from Franciscan University of Steubenville