On a cold day in November, hundreds of people flocked to an arena in Coventry, which has previously hosted gigs by Oasis, Rihanna, and Harry Styles, for an event of a very different kind.

The 500 people who turned out – some from as far afield as Mongolia and Canada – were taking part in an activity less known for drawing in crowds: the Rubik’s UK Championship in “speedcubing,” or racing to solve puzzle cubes at terrific speed.

Rows of tables were laid out in the arena and 15 events took place over three days. Some involved solving the puzzle one-handed, others while blindfolded. Teenager James Alonso won the tournament’s biggest event – solving the classic 3×3 cube at speed with an average of 6.3 seconds.

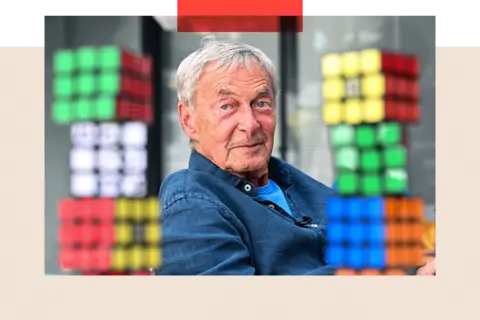

Speedcubing has been popular since the 1980s and the world record for a single solve in that event is currently held by Max Park from the US, with a time of just 3.13 seconds. It is a far cry from the initial speed of Ernő Rubik, an architecture professor, who invented the Rubik’s Cube in 1974 and took around a month to solve it.

Flash forward to today and an estimated 412,000 people have taken part in speedcubing competitions worldwide. The popularity has increased too, with reported global sales of Rubik’s Cube products recorded as $86.6m (£67m) in 2023, up 13.5% on 2022. (The brand was acquired by a Canadian multinational toy company Spin Master in 2021.)

That’s not counting the sales of other types of puzzle cubes by different brands. Some are wooden, others electronic with built-in bluetooth, then there are those with all manner of colourful designs.

But now, scientists have lauded speedcubing, in particular, as not only a popular hobby but one that could have wellbeing benefits too.

“Speedcubing offers a unique combination of cognitive challenge, [alongside] social connection, and personal achievement that contributes to happiness”, says Polina Beloborodova, research associate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Centre for Healthy Minds.

And this is said to run far deeper than a simple momentary rush.

Cubing and happiness: what experts say

“Speedcubing satisfies the basic psychological need for competence, the feeling of effectiveness and mastery,” explains Dr Beloborodova. It involves a number of factors including, problem-solving, memory, spatial reasoning and motor coordination.

But solving the cube may also elicit happiness because it taps into other emotions, according to Dr Julia Christensen, a senior research fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics in Germany. “Awe, beauty, being moved, all these are aesthetic emotions, and experiencing them gives us an extreme sense of happiness,” she says.

“For example, when a pattern is the right pattern, when a move is particularly amazing on the cube, these aesthetic emotions can give transformative experiences.”

Some speedcubers have described the state of mind that the activity can bring as a sense of “flow”.

“This state is achieved when the activity’s difficulty matches your skill level, distractions are minimal, the goals are clear, and feedback is immediate — all of which are characteristics of speedcubing,” says Dr Beloborodova.

Flow can feel “almost meditative”, according to Ian Scheffler, author of Cracking the Cube, who has experienced this first-hand. “You enter this state where you are kind of thinking and not thinking at the same time – you are reacting to what the cube is giving you, but in almost an instinctual way.

“It’s a kind of mindfulness that’s deeply rewarding… a peaceful, calm state where you’re completely in tune with every twist of the puzzle.”

There is good reason to seek a flow state regularly, according to Dr Christensen. “Science shows that people who regularly experience flow have a better mental health, possibly better physical health, and are more in tune.

“When we repeat movements they become logged or encoded from explicit, effort-full memory systems, and pass into implicit, less effort-full, and procedural memory systems,” she continues.

Nicholas Archer, a 17-year-old speedcuber from West Yorkshire, who won the one-handed competition in this year’s UK Championship with an average time of 8.69 seconds, says that he has experienced this. “When I’m solving the cube, I’m certainly not having to think too much about what I’m doing. It’s all automatic.”

Speedcubing social benefits

“Speedcubing or solving a cube on your own may increase your happiness,” says Dr Adil Khan, a reader in neuroscience at King’s College London (KCL) – but when combined with the social aspect, any benefits may be greater.

“Since speedcubing is a social phenomenon, perhaps the social aspect combines with the puzzle solving to deliver a deeply satisfying experience.”

Jan Hammer started speedcubing at the age of 44, after being introduced to it by his 13-year-old daughter. He has since solved the cube around 10,000 times but does not think he would have maintained this level of enthusiasm had he been speedcubing alone.

“The fact that I can do this with my daughter and that we cheer for each other is wonderful. Additionally, being part of the cube community has become a huge motivation.”

Competitions tend to have more children and teenagers – it is not uncommon for competitors to be as young as six. The activity is also significantly more popular with males. The World Cube Association reports that 221,117 men have competed at their events, compared with 24,311 women.

Regardless of demographic, “for those who view speedcubing as a significant part of their life – such as participants in tournaments – it can offer eudemonic happiness, fostering a sense of purpose and meaning through dedication, accomplishment, and community of like-minded people,” argues Dr Beloborodova.

Psychologists differentiate between two aspects of happiness: “hedonic wellbeing,” related to emotional experiences, and “eudemonic wellbeing,” which concerns meaning and purpose in life.

“Both are essential for overall happiness and speedcubing can contribute to both types of wellbeing,” she says. All of this “contributes to better mental health”.

Puzzles and the brain: the science

The effects of speedcubing on the brain and cognitive function are, however, less clear.

While solving a cube, the brain is trying out different moves, asking “what might happen if I move the cube in this way?” explains Dr Toby Wise, senior research fellow in neuroimaging at King’s College London.

“Your brain stores a memory trace for different configurations of the cube, and it can run through different configurations to predict which will have the best outcome.”

However it doesn’t necessarily create long-term benefits, like improvements to memory function. This is because, as Dr Khan explains, the brain is not like a muscle that needs to be flexed to make it grow.

For many years it has been suggested by some that solving puzzles, whether Sudoku or crosswords, can have a hand in slowing cognitive decline or dementia. However this is not necessarily the case.

A study undertaken by Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and the University of Aberdeen, and published in the BMJ in 2018, found that people who regularly do intellectual activities throughout life have higher mental abilities, providing a “higher cognitive point” from which to decline, but that they do not decline any slower.

“Solving puzzles does not improve your brain power in much other than the puzzle itself,” argues Dr Khan. “And almost certainly does not prevent age-related decline in brain power.”

One further benefit of speedcubing, according to regular players, is its sense of escapism from frenzied modern life.

“Having a clear goal, something that you can actually realise, is something that we don’t necessarily have in everyday life, and that appeases our brain,” says Dr Christensen.

This perhaps explains why the cube is so popular in an age with myriad computer games and technological activities to choose from. As Mr Hammer puts it: “When I pick up the cube, I become more alert and focused.”

He uses it in the workplace too. “It can help me enter the next meeting with a more structured perspective,” he says.

Mr Scheffler agrees: “The process of taking the cube from this chaotic, disordered state, which is always different because there’s so many permutations of the puzzle, to the same ordered state is fundamentally something that humans want to be doing.

“There’s a fundamental human need to make order out of disorder, because the universe is a very chaotic place, and most things are not ordered.”

By Tom Gerken & Harriet Whitehead from BBC